Nina Portolan is a para-karate practitioner, microbiology student, and activist for the rights of persons with disabilities. Last year she won a bronze medal at the European Championship in Porec. In her own words, she started practicing karate out of mere curiosity, to find out if she could, and now the sport is a dominant part of her life.

– I had no clear goal, didn’t think I would stay in the sport, nor could I anticipate where karate would take me. Now I am aiming for the world medal. At the same time, I find it valuable to provide things I couldn’t have while growing up to younger people. I had no role models, thanks to which I would know it was possible. The kids we work with today have me as a role model, and I am glad because of it.

With Nina Portolan, we talk about para-sport and para-karate, martial arts philosophy in everyday life, overcoming external barriers and defeating inner enemies, about a skill to go back to herself.

What don’t people know about you, and it’s not a secret?

– I am Disney aficionado. I know it is silly, we are expected to grow up at one point, but it didn’t happen, at least when Disney is concerned. I use my nieces, two and four years old, as an excuse to watch the cartoons again.

How do you remember your childhood period?

– I am grateful for being able to say – freedom. My parents never held me down. No matter how many barriers were there, because of disability or by life circumstances, they strived to enable me to try out everything I wanted. I was pretty free. I knew boundaries, and at the same time, my parents trusted me endlessly – I could go wherever and whenever I wanted. There is a plethora of experience I thank them for because I wasn’t overprotected or pushed aside, and I could count on their full-scale support.

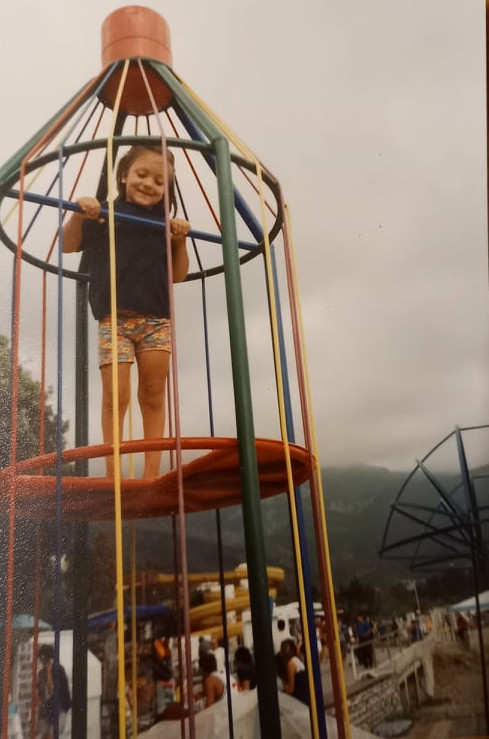

Which childhood memory makes you laugh today?

– I was terrified of heights for incomprehensible reasons but overcame it at a cable car. I was not afraid of falling – paradoxically, I dreaded the elevation but loved climbing. As if, in a way, I was challenging myself. I do it less and less nowadays. As children, we are fearless because we do not think about the consequences. I was a headstrong child, often beating my head against the wall. Growing up, I learned there was something good in a comfort zone. It is all right to stay where you feel fine sometimes.

How did five-year-old Nina imagine her present self?

– During that period, 16-17 years old young people appeared grave and grown-up. If I could have seen myself, I would have probably thought I had already had a family, children, career, lots of things. I had a childish, naive vision of life, imagined that at this age, I would be earnest and grown-up, which is not the case at all. I will be 25 soon, and part of me is still a child.

Who are the most significant teachers, role models, or persons that influenced your choices and the road you are on?

– As far as sport is concerned, it is my sensei, trainer Livius Bunda. He instilled the fearless faith that everything is possible. I came with loads of questions and doubts, and his only answer was: Let’s try! It hasn’t changed for all these years. Whenever I doubt or think we might take on too much, he says: Let’s try! On the flip side, when I want to try something someone else might not let me, he embraces the opportunity: Let’s see what will happen! He gave me wings in the sports sense. Education and academic achievements in focus, my grandma’s influence was unavoidable. She couldn’t complete primary schooling but only did four years. Only when she had moved to Belgrade and become a mother did she go to evening school. Having had that kind of experience, she had immense support for my cousins and me to be fulfilled in an academic sense. No matter what ups and downs I have on the path, she is always there to back me.

How did you start to practice karate?

– For a few years, I did dance classes in a dance center, and I learned the basics but had no support needed to thrive, and I felt overwhelmed. I started questioning myself what to do next. I knew I wanted to train something and be active but didn’t know which way to go. By chance, my mum brought a flyer from a copy shop which said: Karate lessons for persons with disabilities. I found it interesting but not really a sport for a girl. I have a heftier body and didn’t think of myself as very feminine, so I thought karate would make it worse. I thought about it for a few days, and since the club was in the neighborhood, I decided to contact them. There was no answer for a few days, so I was sure nothing would come out of it. When the trainer phoned me, I told him that I had never done anything close, that I would come for a trial, and at the very end of the conversation, that I used clutches. He answered: OK, come in to try. It is how everything started. For the first couple of months, I wasn’t sure if I would stay. I wasn’t a martial arts devotee. I simply fell into the sport. Over the years, the dream developed, and now I can see it clearly ahead of me. I am completing a trainers course and planning to stay in the sport for a long time.

Did karate contribute to building a picture of a healthy body?

– Absolutely, contrary to all my expectations. I think that strength, not just physical but mental, and the stability martial arts bring led to manifesting my feminine side better. At the same time, I am much more confident and have more self-assurance in my body and appearance as a consequence. It is a process, maybe we are never satisfied completely, but now, when I look at myself in the mirror, I am much happier.

Who is not for martial arts?

– Someone not having the willpower to work hard; cannot accept that they are wrong on occasion; and that everything is not possible at once. That’s it. Martial arts demand a lot of patience and firmness of character, and that is something one learns. I am irascible, and years of doing karate taught me not to be. Whoever wants, can do it.

What are your worst inner enemies, and how do you prevail?

– Anxiety that I have been fighting for years, outside the sport as well. There is also the fear of failure, not so much in the sense of personal disappointment, but in the sense that I will betray the invested work, and it is a lot of work. They are the little devils on my shoulder that sometimes before I go out on a tatami whisper: – You will break now; you won’t do anything. All the work and effort invested in you are going down the drain. It is just a tiny voice in my head that won’t be quiet on occasion, and what it is saying is not based on reality since I had support even when I was losing.

How does your practice differ from the karate of a person without a disability?

– It doesn’t differ at all. I have been training in the karate club Europe from the beginning, within sports karate association for the person with disabilities in the inclusive group. The only difference is that I compete using a wheelchair because the World’s Karate Federation’s rule book says that competitors that cannot stand or walk independently use a wheelchair. There is a tendency to change it, but it is a rule for the time being. We all do the same things in practice; the only difference is that I sometimes use a wheelchair. The approach might be different because we need more support to try the sport in the first place; adaptations are individual and done on the fly. A sportsperson could have an accident; for example, break an arm. During an injury period, he would be doing the techniques with one hand while the training remained essentially the same. The competing process is different since para-karate practitioners have fewer opportunities to show their skills. I wish the organization of the competition would be more inclusive. For example, European and World’s Championships are inclusive now, meaning that karate and para-karate competitions are held at the same time and place; this enables us to interact, train together and communicate. When I first went to the European Championship, which was held in Novi Sad in 2018, the competitions were separate, and the last two days were reserved for para-karate. Up to that moment, all the other competitors had gone home. I am glad that they changed it. The rule book is also adjusted, meaning it is the same for everyone; the same rules apply to all. There are a few inclusive competitions; we cannot enter many tournaments because there are no categories, no para-karate organizations, no referees, nothing but closed doors. I hope it will change in time; the para-karate has only been developing in the last ten years.

How much does the philosophical aspect of martial arts help you in some other life aspects?

– A lot, indeed. I would love to be asked about it more. Everyone finds it intriguing how I do it physically, but the fact is that it has changed me mentally. There is a Bushido Code, a samurai code, based on honor, respect, and values that are scarce in everyday life nowadays. Simultaneously it teaches us to be calm, to stay grounded. It means that you grow roots- whatever happens around you – doesn’t happen; it is blocked out. Everyday life is unpredictable, but I learned in time to some extent, to reach a mental state as when I step on tatami and the audience and a referee vanish. I am focused on myself, don’t hear or see anyone, am inside myself and my own. The skill to go back to myself and inside is of the utmost value in everyday life, especially in a crisis. We often go back to take a deep breath, close our eyes, ground. I go back to myself. I learned at the same time to channel my anger.

What do you see as your greatest accomplishment so far?

– The first medal I won is the most vital, despite the fact it is the lowest. It was in 2017. at a small trial tournament. There were five contestants, but I still cherish that feeling I had when I climbed the pedestal. Objectively speaking, my greatest achievement is a bronze medal from the European Championship in Porec 2021.

And what is your greatest disappointment?

– Considering the misapprehension of the Federation or the contestants without disabilities, I may say we are exposed to disappointment daily. We used to have the support of the Belgrade Karate Association, Karate Association of Serbia, Belgrade Association of Sportspersons with Disabilities; we have good communication with the representation, but we often face barriers and misunderstandings. My greatest disappointment was the European Championship 2018 when I lost the bronze medal for 0,1 points. Losing is a part of the sport, but it was a cold shower.

Have you ever had a period of doubt, been in a dilemma, or were on the verge of giving up?

– At the end of the previous year, I had COVID-19 and was out of shape. It lasted for a month. In the meantime, some people dear to me left the club, isolation due to COVID exhausted me mentally, and I felt I was losing my stability. I took a long break, I couldn’t go back to training at maximum capacity, so I wondered if it was worth continuing at all and how. I talked to the trainer, openly telling him how I felt, and he answered: – Well if you don’t feel positive energy now, make it yourself. I felt angry at the comment because I didn’t believe I had the strength to change the atmosphere. It turned out I did; the trainer was right. I made myself go to practice, and everything went back as it used to be. In a week or two, I saw that the situation was not as bad as anticipated.

What motivates you?

– As for karate, I already have a deep inner motivation; it is so deep that I can’t verbalize it. I have unconditional support from my trainer, the atmosphere in the club is good, all of that is wind at my back. There is a flame inside me that doesn’t let me give up, no matter what. Actually, I learned how beautiful life is through the toughest moments in my life. It can be terribly painful and difficult; something occurs and breaks us. But there is a silver lining. When enduring a difficult period and losing motivation, I remember thinking before that nothing better would happen, but it did and was much more than I could imagine. It is a cycle. When I don’t have motivation, I go back to beautiful moments, my family, and the people I love. I do not give up because of myself, them, all the love I have and that is yet to come.

What do your mental preparations look like before going to a big competition?

– They put me in unpredictable situations to release me from anxiety as much as possible, of stress and habit to be in my gym, in my dojo, in my safe space. For example, the trainer might take me to the park to practice. It might appear funny, but it is very significant for my mindset because I shouldn’t care if I train in front of passers-by in the park, in front of the building, wherever. During that period, the focus is on competition everything else can be put on hold. Just before the competition, we don’t practice intensively- as a matter of fact, pieces of training become lighter, and the focus is on concentration and stress elimination. Our coach likes to say: – We are going for a medal. We learned that it doesn’t mean he would be disappointed if we don’t win one. Whatever happens at the tournament, we necessarily go somewhere to relax together. All competitions bring pressure, which is inevitable. I had an opportunity to talk to a top sports psychologist, and we worked on psychological preparation, but I do not need continual professional help in the field. The coach and I know and understand each other very well, so we can solve numerous things on the spot.

How do you deal with the defeats?

– It is hard for a moment. I can say that by some crazy luck, there were a few. In the beginning, when it wasn’t easy dealing with the defeat, I was winning medals because there were a few of us in the competition. It happened that in the first few tournaments in my running, there were no competitors, except for two or three of us. The situation is lucent in that case. There are more of us nowadays, so it doesn’t happen anymore. But I don’t see defeat as defeat any longer. It gets tough; I get disappointed and angry with myself, especially when I know I could have done better and didn’t because of jitters. I feel bad for a day or two, but I’ve learned in time to watch the contestant that defeated me and wonder: – What can I improve to get to her place? I can learn something from each loss. I met a current European and world para karate champion, Isabel Fernandez, in the championship in Porec. She came up to me in the preparation gym and said without hesitation: – Listen, you need to shift this band on your wheelchair. Your knees are sleeping and making it difficult to exercise. She approached me again during the competition because it happened that my coach was on another tatami, with another contestant, leaving me alone since I was more experienced. Isabel saw I needed support, tapped my shoulder, and said: Go on, you can do it! It is that energy: outside of tatami, we are not adversaries. I lost a fight to Isabel; she is more advanced. I watch her and think: – What does she do better, what can I learn from her?

How demanding is it to do sport professionally and study molecular biology?

– It’s very hard. I had enrolled at the university and started training soon after, having no idea what endeavor it would be. The interesting fact is that Biological Faculty has no premises; we are nomads. Since we use the rooms of other faculties, walking marked the first two years of my studying, which made me more tired physically and harder to train. In some periods, especially during exams, it is very difficult, because I know that I have to stay in training. I cannot afford a break at the moment since the European championship is in May, which is around the corner. Due to some other life circumstances, I have prolonged my studies; this is my seventh year at the university, and there are a lot of unresolved bits and pieces and exams. Professors whose lectures and practice work I missed because of competitions were understanding about my non-attendance. But the studying system of Belgrade University is such that it doesn’t allow much space for two parallel carriers. Balancing it is not easy; on occasion, I need the day to last for 48 hours.

What are the things you have to deny yourself in a moment because of long-term goals?

– I try to achieve everything not to miss out on pieces of training, college, socializing, or free time. But at times, I have to say no, to give up mixing with friends or rest. I tell myself: – Keep it up for a few more days – it will come. It is a sacrifice, but I don’t want to give up. We all need a social life, time with the family – it is all about balance. Unfortunately, I am not very organized, so sometimes I wonder how I manage to do it all. On occasion, it is just: Keep going!

What is, in your opinion, most fascinating about molecular biology?

– We studied genetics in high school. I was absolutely fascinated. I found it so interesting that I started looking for textbook examples in real life to see how we inherit a particular trait. This interest guided me, although there are less interesting things at the university that make you change perspective. Considering molecular biology and molecular mechanisms in a cell, I find it fascinating how fragile they are; how delicate we as human beings are because a tiny change in a genetic code can have immense consequences. Also, how simple the protein synthesis is and still plays a great role without which we wouldn’t exist. All of these arouses a childish curiosity in me to ask how and why things happen.

How accessible is the academic community, and what kind of barriers do you face being a student with a disability?

– The shortest answer possible: it is not accessible at all. If I were a permanent wheelchair user, I wouldn’t reach the faculty because the rooms are on the second floor, an elevator is in the other part of the building, unreachable without using the stairs. If I were a permanent wheelchair user, I wouldn’t stand a chance to study Molecular Biology. Accessibility is not on a satisfactory level, not even close, starting with the public transport, lack of literature in Braille and induction loops, existing architectural barriers. Furthermore, there are no texts in simple language for persons with intellectual disabilities who have no chance to complete higher education in our country. The system itself is inaccessible. It is not difficult to put a text-to-speech device or a sign in Braille in the elevator, but nobody thought about it. I tried to initiate the topic at the beginning of my studies, the whole thing reached the Rectorate, but I have never got an answer. The academic life of students with disabilities is reduced to individual initiatives and find a way.

Where do you see yourself after your studies? In the gym or the lab?

– Sport. I used to think that I would end up in a laboratory. Over time sport became my preference, especially now, when I started a course at the Sports Academy to become a coach. I might stay in the academic area, but within the sport, to apply knowledge from biology to biomechanics.

You were engaged in the European Network on Independent Living (ENIL). What did you do there?

– I become an ENIL volunteer through European Solidarity Corps. The engagement lasted for nine months during 2020. I am still a member of the network, and we cooperate on a need-to basis. I should have gone to Brussels, but Corona ruined the plans, so I fulfilled the engagement from a distance. At the end of 2019. I received an invitation to the European Commission honoring the Day of Persons with Disabilities, which was an opportunity to make contacts and get to know colleagues. Working at ENIL has shaped me to a great extent. I was engaged in the research of the rights to independent living on the territory of the member states of the Council of Europe. It was a huge endeavor. Numerous gaps in the system sprang up, but simultaneously some examples of good practice as well and I learned to look at things from a different perspective, and when I reach an obstacle say: – It is doable! Specific rights have been exercised in this and that state. I got to know the philosophy of independent living and the social model of perceiving disability – that was an entirely new concept for me. I am grateful for that. I am proud, not only of the project I managed to complete but also of the fact that now, in my daily life, I can apply the learned principles, and advocate for the rights of people with disabilities.

Are you a member of some association for persons with disabilities?

– I have been a member of the informal initiative IM-PACT 21 since its establishment in 2021. Until recently, we have been working on a project about the availability of aids for persons with disabilities in Serbia. The slogan was: Aids is life because they really are. From my personal experience, it took a long time to comprehend it. I refused to use a wheelchair or crutches for a long time. I perceived the wheelchair from an able point of view, looking at it as a sign of surrender. I thought if I could walk, and I used a wheelchair, that meant I didn’t try hard enough. It has been a long journey, but now I know that aids bring us freedom and I use a wheelchair from time to time. It started at tournaments where I faced the need to use it for the first time. After a few months of psychological turmoil and struggle with myself, I wondered: – Why are you not helping yourself? You ruined your shoulders by trying to walk even when you can’t; your knees, joints, everything is under pressure. Why do I refuse a thing meant to help me? It is how I accepted the wheelchair. I use it when I travel, for long distances, when I feel I need it, and when it is architecturally possible. Lack of access to appropriate assisting devices prevents us from functioning as we would like to and becoming fulfilled. A report on the subject will be published soon, and we hope for changes in the regulations of the Republic Institute for Health Protection.

How satisfied are you with the media attention para sportswomen/sportsmen get in our country?

– Para sportswomen/men are not as visible as they should be, although I notice it is changing slowly and the interest is growing. I remember reading a study on what the general population thinks about para-sport. Most respondents said that para-sport diminishes the sport, whilst only 2% of them watched any para-sport. It shows where the problem lies. Everyone says that para-sport is not a sport, but they have no opportunity to see para-sportswomen/men. We definitely need space in the media to educate the public that para-sport is no lesser than sport. If we can meet sportswomen/men on the balcony, we can meet para-sportswomen / men there too. Each big success should be celebrated.

In what way would you empower girls with disabilities to practice sport? Or better yet, anything they would like to do?

– Maybe we cannot make top results in a chosen area, but we can be happy. The pleasure we get from doing something we love is more important than any success. When the environment and circumstances say no, a bit of stubbornness and faith comes in handy. Something may appear elusive, but there is someone in the world that did it. If it has never been done, be the first one.

Anything I haven’t asked you and is significant to add?

– I asked the coach once why we should perform if the audience would leave before we started. He said: – If out of a thousand of people watching, nine hundred ninety-seven leave, three would stay. The three are a good enough reason.

Photos: Nina Portolan’s private archive

Translated by: Suzana Belos