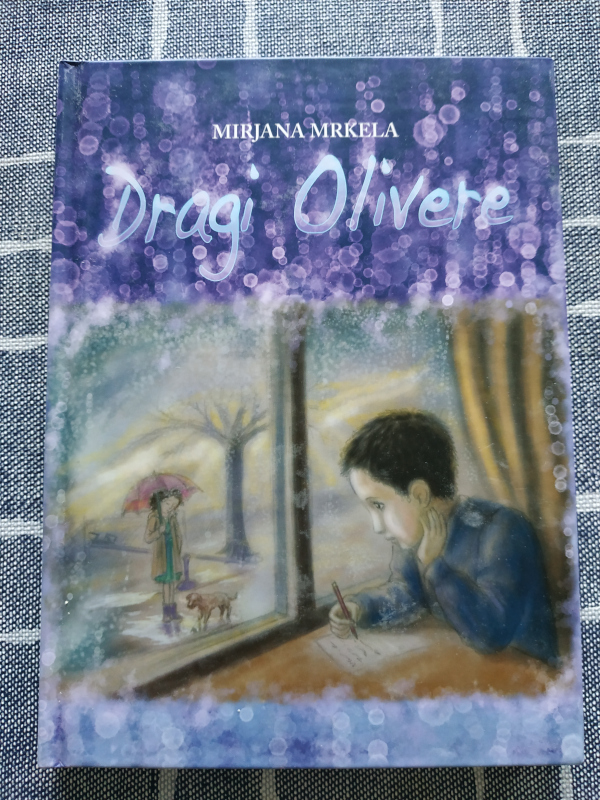

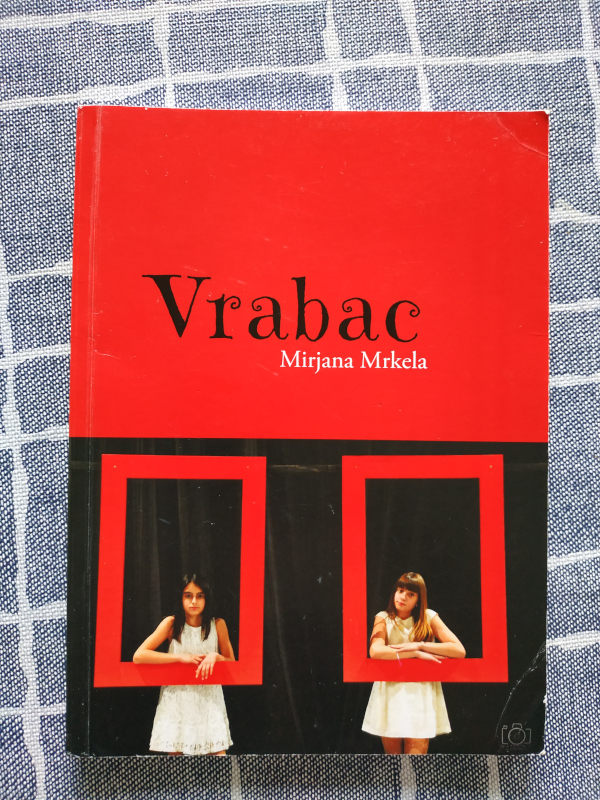

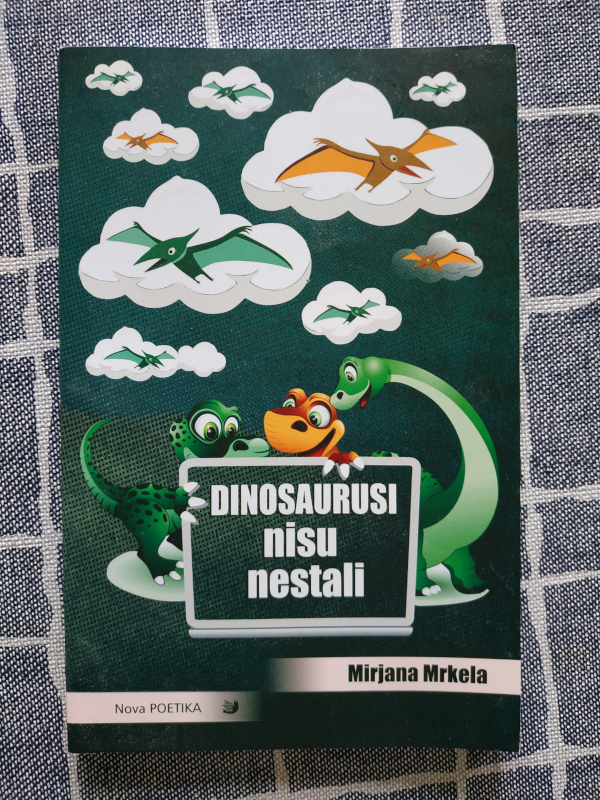

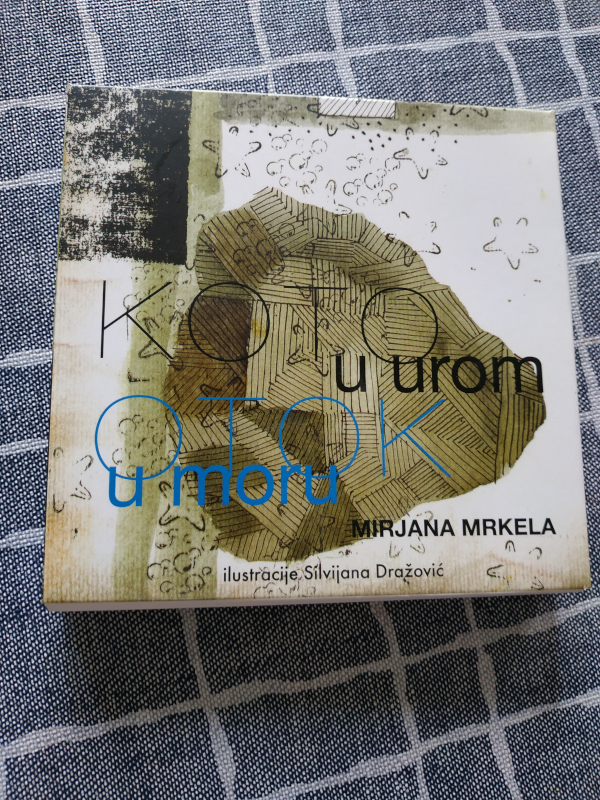

Mirjana Mrkela, a writer from Zadar, is the author of numerous children’s books and the laureate of the Grigor Vitez prestige literary award. She writes novels, plays, stories, poetry, and reportage. Her work was broadcasted on Croatian Radio, published in magazines and web portals, and can be found in school textbooks. Her published books are: Dragi Olivere (novel), Ljubavne pjesme (poetry), Mea mlađa sestra (novel for teenagers), Moja zadarska čitanka (anthology for children), Upoznaj izume Fausta Vrančića (didactic cards), Putovanje naslijepo (Baedeker), U zemlji Plaviji (didactic stories), Vrabac (childen’s stories), Bob bobić mahuna (illustrated anthology of stories), Tun pristani, kapitane (picture book), Koto u urom (literary – fine art map), Stand here, Captain (picture book), Mi smo dva svijeta (poetry), Upoznajte prirodne ljepote Zadarske županije (informative – educative cards), Dinosauri nisu nestali (anthology of children’s poetry). Mirjana Mrkela is a permanent contributor for the bimonthly magazine Riječ slijepih and the Internet magazine Kvaka. She is a member of the Croatian Writer’s Association, the Croatian Children’s Writers Association (The First Writers Club), and the Association of Writers from Zadar (ZaPis). She is active in The Blind People’s Association of Zadar county. For The Disability Portal, we talk to Mirjana Mrkela about life, literature, creativeness, and literary cravings, teacher’s and reader’s habits, sensory disability experience within the literary scene and out of it.

What is not common knowledge about you and is not a secret?

MM: Since I am extroverted and imposing, it is difficult to answer this question. When I was little, I wanted to become a pilot. Simultaneously I yearned to go to school, wanted to be a pupil. In a way, I am both today. In other words, my dreams have come through, but differently from my plans.

You were born in Belgrade. What are your memories of that city?

MM: Plethora of memories. I lived there until I reached adulthood. I was very lonely as a child and didn’t fit in as a teenager. I often visited theatres and bathed at Ada Ciganlija.

What fascinates you most in Zadar?

MM: Everything. Rocks, the sea, parks, air, the mixture of past and present, a blend of good and bad people – bad ones to be scolded and gossiped about, good to be admired, and as role models. Zadar is a kind of cocktail that suits me perfectly.

What did you use to like to read as a child? Which literary character did you find the easiest to relate to?

MM: My first was Tvrdoglavo mače by Bjelišev: the kitten had some awful time alone in the woods. Then came Andersen. Gerda and her friend Thumbelina – I wished to be one or another interchangeably. I wanted to help the little match girl. I imagined the ways to do it and this year I’ve finished a novel about it.

If you could send a message to yourself to some point in the past, which one would it be? What would you ask her?

MM: He-he, it is like in a joke about a virgin, that after she died, is sorry she was so virtuous. But to be serious, I do have some villanies on my conscience. That is why it would say:“ Mirjana be nice, be tolerant, be understanding. The same I ask from others today.

Selimovic called writing the need stronger than benefit or reason, ruthless scrutiny, devil’s trade, and inevitability (like living or dying). Can you relate to these words? What does writing mean to you, and what drives you to do it?

MM: Mesa is one of the authors I admire most. I especially like his Fortress. But I am not a big writer, and my writing is no so sublime. First and foremost, it is the way to express myself, topped by the need to read, eternal craving for nice literature, either written or recited or performed in theaters.

You write novels, plays, stories, poems, and reportage. What did you write first, and how did you find the authentic voice which singles you out as a children’s author?

MM: I had to do it. When I lost my sight, I was compelled to fight for my bare existence. Since I was a primary school teacher, I was aware that there are not enough short stories for the first and second grades, so I wrote those and sent them to magazines. Editors encouraged me and, that is how it started. Children are not stupid, they just know fewer words, and they consider things differently. They know many things we have already forgotten and will learn stuff that will remain unknown to us.

How much does your professional teaching experience help (or hinder) in writing for children?

MM: I have already answered the first part of the question. However, teacher’s habits can be a hindrance. I am prone to being too tutoring. In other words, I tend to patronize, lecture, and finish the conversation.

After becoming disabled, you stopped working in education, and today some of your work is in school textbooks. What was happening in the meantime? What were the breaking points in the process of excepting your disability?

MM: I started excepting life with a disability when I was told that I was truly blind. As far as writing is concerned, the breaking points were computer usage and when my book was published. The first one helped me realize that I can, the second showed the others I can. The thing that was left is that the others were the whole world.

Do you think that the experience of sensory disability influences the poetics of your work? For example, you are the author of the travelogue Putovanje naslijepo (Blind Travel). Would the book be any different had it been written before you lost your sight?

MM: I wouldn’t write that book for sure. A lot of people told me that blindness could be my particularity, but I am very circumspective. Travelogues were written for blind people in particular, and now I have a regular column in a magazine It is Better that I don’t See. But that is only one aspect of my interest. I have been maturing as a writer. Recently I have been working on a novel about a blind woman in which I am using a lot of stuff I have experienced myself.

Illustrations have a significant place in children’s books. How do you work with the illustrators? It is common knowledge that visually impaired people can do visual arts (photography, painting). How much do you participate in or give suggestions about illustrations for your books?

MM: Depends on the occasion. It is important to me to know the illustrator, his sensibility. Sometimes I suggest something, and sometimes I argue my point. For instance, dialogue about the book that is being done at the moment.

I: I was told that my elephant boy looks scary.

Illustrator: God, what elephant?

I: The one sitting on the fish.

Illustrator: Oh, that is Pinocchio on a whale.

I: Anyway, I don’t want Pinocchio. And the nose, looks like … (obscenity)

Illustrator: Woman!!! It’s a children’s book.

I: My thoughts exactly! (laughter)

Illustrator: I was bad-mouthed. O.K. You persuaded me to move Pinocchio into another book.

In your opinion, is children’s literature underestimated? Have you ever had doubts about the value of your work?

MM: Yes, it most certainly is. It’s like it is not art but commerce with picture books. I blame literary theorists for that, but all the others as well. Here in Zadar, the situation is catastrophic. Except for myself, there are no authors that published more than three children’s books. As if it is a disgrace to be a children’s author. They have been lenient towards me because of the blindness and perhaps because I am tenacious.

Can you remember how many times the publishers rejected your novel Dragi Olivere and how did they justify it? How did you, despite them kept your faith in the manuscript and the urge to give it up?

MM: I have been sending the number of copies by mail or post. I have received a few replies saying the time is not appropriate or the book is not following the program. Then the year of Charles Dickens was honored, and I thought it is now or never. My book needs to connect with Oliver Twist. I spent the first part of the year negotiating with a publisher. They told me that I needed to pay for everything myself. I said O.K. I’d publish it myself. I sent 20 e-mails to publishers and editors who could have some idea of who I am, the contributor to children’s magazines. Nineteen of them did not answer. The twentieth one, my dear friend nowadays, Kata Ivankovic Maric, wrote shortly: Mirjana, I will help you. Then I got a loan from the bank, which was a huge burden for my monthly income and paid for the printing. Testa dura (hard head), as Italians say.

You’ve been given the prestigious award Grigor Vitez for that very novel Dragi Olivere. What changed in your life after getting the award?

MM: My self-assurance has become much higher. It is a bright star in my biography. However, I don’t think I have materialized it well enough. I have missed some opportunities, either because I didn’t recognize them or because I didn’t know how to benefit from them.

Original fairy tales are of the utmost significance for the psychology and development of a child. Nowadays, we witness a new trend where cruel parts are erased as inappropriate for young children, that they are retold and often made trivial by shallow explanations. As a fairy tale author, what can you say to defend a genre?

MM: I consider myself to be a writer of fairy novels. Brothers Grimm, Andersen, and Charles Pero wrote fairy tales. Of course, there are folk fairy tales, inarguably many of them cruel, mentioning alcohol, cannibalism, ruler, and male despotism. All those things serve a purpose in fairy tales, are justified, and are what they are. To cut a long story short, I think it is needless to shield children from reading about cruelty. We need to protect them from experiencing one.

What does it mean to write a contemporary fairy tale, and how are they different from the ancient ones?

MM: Real fairy tales have depth and layers. However, nowadays children are offered many different things apart from storytelling. Bookstores and stationery shops are everywhere, interactive games, films, and galleries are ordinary in most of the world.

In the magazine Kvaka you write reviews for children’s and teenagers’ books. How do you recognize exceptional literature compared to the average one? What is your general criteria to choose a book for the recommendation? Which five books would you choose at the moment?

MM: My main idea is to get the children to read something that is not compulsory school reading, even artistically median. Unfortunately, I rarely come across books published outside Croatia. Still, I am familiar with many of them. For reasons mentioned, the column is for the readers visiting Croatian libraries, which lack many authors. Not the same books get translated, and the children from other countries don’t know the titles that are part of the compulsory school readings in others. Five works are too many, I’ll name three. One of the very first I have written about is Ljetovanje sa čovjekom koji nije moj tata by Vlado Rajačić. I’ve also written about the book popular when I was a child: The War of the Buttons by Louis Pergaud. I am exceptionally proud of the correspondence with the New Zealand writer Witi Ihimaera, author of The Whale Rider. If you cannot get the book, at least watch the movie.

You are active in The Writers Association of Zadar (ZaPis). Do you take part in writer’s workshops? What happens in interactions with other authors? Is four-hand writing possible?

MM: Yes, it is very convenient that you linked the two questions. When something is done in a workshop, almost always is done with more than two hands. Of course there are some adamant writers but, they soon realize they don’t need cooperation but admiration. They need to seek it elsewhere. The encouragement that writers receive at the workshop is not just mere praising, at least this is not how I see it. We all love to hear: “ This is great, right to the center, it is inventive. “ etc. As for writing in a pair, I do have experience in writing poems. I encounter it as something intimate and sweet, and I am ready for business cooperation too. I am not selfish as a writer – I am open to discussion and easing up. Members of the ZaPis are like next of kin, something in between friends and siblings.

You are a member of the Blind People Association of Zadar. Tell us something about it, and why is it important to be a part of it?

MM: When my daughter was young, I was given an excellent piece of advice: „Let her see that you are not the only one with that disability.“ Apart from the child, I benefited from it too. Blind people are the ones I understand, although we differ as persons. Blindness is not the only trait we have. Regarding the association, it functions the best if someone is pulling ahead. In our case, it looks like it is the girl we hired last year. Everything is much livelier with her. We write projects, cooperate, hang out, etc.

How easy is it to go to literary events, promotions, festivals, and book fairs? Do you face discrimination in the literary scene?

MM: There is no discrimination. The proverb says: where there is a will, there is a way. Only if I knew Braille, I would read something when I feel like it. I am very fond of fairs, lectures, and presentations, direct contact, and conversations. It is not because of the handicap that is my disposition.

If you could change a thing in our society, what would it be?

MM: Nonviolence, demilitarization, pacifism. Union is strength.

What book do you still have to write?

MM: Better than any I’ve written so far. More affluent, more original, more interesting, and probably more honest.

Anything you want to add that I didn’t ask you and is substantial?

MM: I do not like waiting. Probably that is why there is a lot of it in my life. Or perhaps (sometimes luckily for me) not everyone is as resolved as I am. Thank you for the questions. Some of them encouraged me to make some new findings of myself.