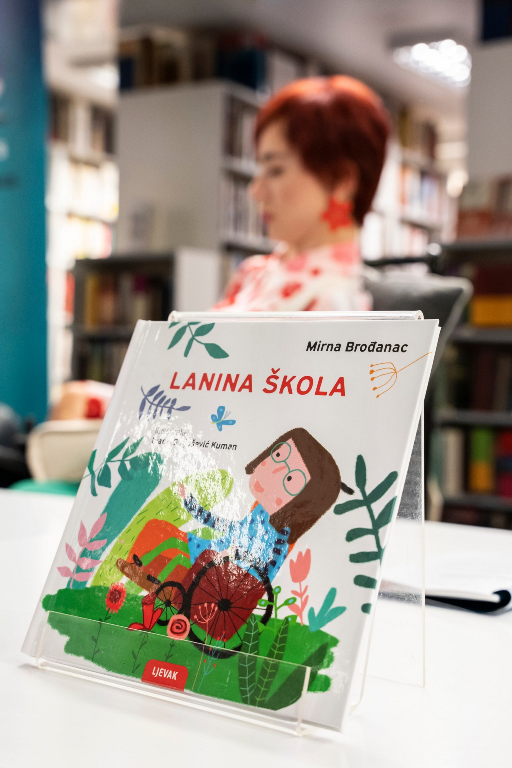

Mirna Brodanac (1992) is a high school teacher of Croatian language and literature, a comparatist, and a librarian. She completed her studies at the Faculty of Philosophy, Zagreb University, where at the moment, she attends a postgraduate doctorate study in Information and Communication Sciences. Her short stories are published in magazines and on portals; she wrote literature critics for booksa.hr, took part in creative writing workshops, and published poetry in a joint collection of poems of a group of female authors – Povezija (2022). Mirna is the author of a recently published picture book Lana’s School, made within the project, Every Story Matters, a project that fosters inclusive literature. Lana’s School is the first picture book in Croatia that deals with the experience of starting school for a girl with a disability.

Talking about herself, Mirna says she is a writer in the making and identifies being a daughter, a sister, a niece, a passionate reader, and a person with disabilities as parts of her identity. Literature is not a mere professional choice; it’s a lifelong devotion for Mirna Brodanac.

– Everything in my life is connected to my love of literature. Literature is my dream, road, and tool that helps me make life worth living in this very skin – says Mirna.

We talked with Mirna Brodanac about her besetting topics, engaged literature, creative processes, and published books.

You’ve completed a double subject study, Comparative literature, and Croatian language and literature, and you are currently studying for a doctorate at the Faculty of Philosophy in Zagreb. Based on your experience, does the academic environment support and nourish literature creativity of young people or, on the contrary, inadvertently suppress ingenuity?

– In my opinion, the academic society is much more burdened by the Bologna Process than was conceived. The students count the ECTS credits and professors their truancies, forgetting jointly the primary motivation, which doesn’t leave much space for creativity. There are always exceptions to the rule; unfortunately, they are rare.

You write poetry and short stories and currently are writing a novel. What is your primary literature choice, poetry or prose? Do you leave space for a literature experiment?

– I am more sure of myself as a prose writer. Poetry indeed is a kind of an experiment for me that I need as someone who only in writing finds true freedom. It has always been more arduous to write a poem than a story and trust that it is good. That is why poetry makes me happy. I like leaving my comfort zone and indulging in playing with language differently and thinking differently about the world and myself. As a matter of fact, when I reanalyze, everything I ever wrote came from an experiment because even when I have a plan, text and life do their thing and take me to unimaginable spaces. In reality, I cannot jump, but indeed I jump while writing. It is a unique and unaccountable experience.

What are the themes that obsess you?

– All my characters are outsiders, and the main characters are almost always women-women from the margins. Therefore, my obsessive theme would be – The position of different people in a patriarchal system and their attempts to find their spot under the sun. The topic can then be branched out to smaller ones as they are: body, especially body as a subject of shame, lust, and violence. The silence that, as Slavenka Drakulic wisely states in her novel Marble Skin, could kill; the phenomenon of freedom and where are its limits; and of course, love, from which people are fleeing helter-skelter lately. It might sound credulous to consider love an obsessive theme, but my brother often tells me that I am a woman that doesn’t necessarily need a partner because I am in love with love, and he is not totally wrong. Dissecting the phenomenon of love makes me fulfilled. By writing, I prove to myself and others that love could be transferred transgenerationally easier than traumas.

How important is it for you to thematize the experience of disability in your literary work?

– I can’t get out of my skin, and it’s marked by disability. For this reason, that experience is omnipresent in my works, but it is not always paramount since they are thematically multi-layered.

Can the insisting on engaged literature kill literature? What is your stance on that?

– The world is collapsing into a dark abyss, and we need engaged literature more than ever, which is proved best by the positive reception in the whole region of an astonishing novel by beloved Ivana Bodrozic – Sons and Daughters. Engagement empowers the literature and enables it to evolve from a proper text with which a reader fulfills their free time to become an initiator of change in this region burdened with hate. In my humble opinion, it is brave, risky, and above all, necessary action to establish new, solid foundations for happier living for those who come after us.

What is the greatest enemy of your writing?

– The greatest enemies of my writing are lack of time, too high expectations I set for myself, and an insecurity worm eating through the motion of the text.

Which authors and books have a special place in your reading experience?

I draw out something good for myself from each book, but I always recommend the following, and if I manage to get some, I bestow them: Milan Kundera – The Unbearable Lightness of Being; Arnon Grunberg – Tirza; Slavenka Drakulic – Frida’s Bed; Azar Nafisi – Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books; Aneta Vladimirov – You Cannot Kiss Hell Better; Han Kang – The Vegetarian; Olja Savicevic Ivancevic – Adio Cowboy; Julijana Matanovic – Notes about an Author; Darko Cvijetic – Why do you Sleep on the Floor; Dubravka Ugresic – The Ministry of Pain; Primo Levi – If This Is a Man; Miljenko Jergovic – Mama Leone; Irena Vrkljan – Berlin’s Manuscript; Jasminka Petrovic – About a Button and Happiness; Betina Ilic – Peter’s Forest; Alice Walker – The Color Purple; Ivica Prtenjaca – Uzimaj sve sto te smiruje; Mirela Gaspar – Spori odron; Ivana Bodrozic – Sons, Daughters; Magdalena Mrcela – In-between; Andrijana Kos Lajtman – Plava i smedja knjiga.

You used to write literary critiques for booksa.hr. Thanks to the internet, social networks, and blogs, anyone can publish a literature review, commentary, write-up, or critique, regardless of their analytical skills and literary-theoretical knowledge. In addition, it appears that contemporary critique (if it is critique at all) is more in the service of marketing and sales than in the service of quality literature. How do you see literary critique today; can everyone write it, and what makes it meaningful?

– Every critique, including literature, is deeply subjective, and that makes it questionable, in my opinion. There are no established criteria for meaningful literary criticism; I think any literary criticism that manages to persuade the reader to dedicate their time to a particular work, whether positive or negative, is meaningful. The important thing is to bring the reader around to reassess the critic’s point. Right, anyone can make a noise and express their opinion, but not everyone can write a substantial literary review. I believe that good writers and dedicated readers know how to recognize a good critic because they all somehow fit in these three roles.

You are a Croatian representative at the international project under the patronage of the European Union, Every Story Matters. How would you present the project in short and your part in it?

– Each person has a right to discover literature and create stories, regardless of their socio-economical or cultural background, sex, sexual orientation, or mental and physical abilities. Having said that, we don’t have the same potential for it. We can see the discrepancy clearly if we peep into the books we grew on. In spite of the fact that we all know that children deserve heroes they can identify with, there are almost no such characters for children with developmental difficulties or young with disabilities. They are scarce in the whole of Europe. European creative project ESM is the best change that could have happened in the European literature for children and young. It enabled six of us, completely different creative people, under the leadership of our great mentors, to write/illustrate inclusive stories and give children and young characters we lacked in our childhood. By creating different stories, we have built a unique friendship mightier than any border or prejudice. If you ask me, such fellowship is the most beautiful thing people can experience.

Olja Savicevic Ivancevic is your mentor on the project. What is the most valuable thing you have learned from her?

– Ola Savicevic Ivancevic taught me that the book’s success begins with my own confidence in the power of the story I have written and the belief that the story is part of the aforementioned engaged literature, which tends to be a bridge between people.

The result of your creative cooperation is a picture book Lana’s School. How did it come into being, and how is it different from other stories and picture books for children?

– Two years passed from the first sentence to the printing of the book. It was written during the challenging times of the pandemic, but with lots of laughter, goodwill, and Olja’s patience. It is the first picture book in Croatia that tells about the first day in school of a girl with a disability. My great wish is that it becomes educational material in schools to help excited students to overcome challenges of mutual exception.

This year, a collection of poems by attendees of poetry workshops was published under the leadership of poets Aneta Vladimirov and Betina Ilić, entitled Povezija (Poetry + connection), in which your poems are also represented. Tell us about your workshop experience, joined creative processes, and cooperation with the other poets. How did you decide to enter poetry workshops; why are they important, and how will you remember them?

– Povezija was published this year in April. Describing the workshops to someone who hasn’t participated is not easy. They were small Saturday miracles of female poetic energy and synergy. Aneta Vladimirov is a loyal friend that continually stimulates me to move boundaries of my consciousness and research how far I can reach regardless of physical limitations, fear and shame. I found it wonderfully helpful to see what we could accomplish together if we put everything into a poetic context. For this reason, I enrolled in poetry workshops, where I got the furthest to my true self. It is an insight that will shine in me forever.

Where does the title Povezija come from, and what is the thread that unites the poems within the collection?

– The ingenious title exactly describes how poetry has connected us (Poetry + connection in Croatian). It was thought of by our lovely Betina Ilic during group work on the manifest. The poems are united by the amalgamation of our different poetic voices into one roaring scream that stops silence and annuls shame. Each poem echoes that scream, eye-opening for the readers and healing for us. To be healthy, artists have to be loud.

How does it feel after publishing a book? Content, euphoric, drained, empty, or something fifth?

– Each time I pass the square in front of the bookstore Ljevak, I stop and watch the picture book trying to convince myself that I am not dreaming the life I am living. At times it looks like I am an observer waiting to see the outcome. I do not dare rejoice as much as I could because we live in curious times. When historical atrocities happen in your vicinity, one simply has to be careful with happiness.

What else have you planned to do by the end of the year?

– I plan to collect enough points for next year’s doctor’s studies, travel on two trips, promote Lana’s School in my old primary school, finish my first poetry collection, and have a party with my closest friends by the end of the year.

Anything I haven’t asked you but is material to add?

– Finally, I would like to point out that I profoundly believe that for all people, and especially for us persons with disabilities, the most important thing is never to accept the role of the victim. We need to do everything in our power to be in the eyes of others first and foremost what we are to ourselves; make our disability just a detail that does not burden us. Perception of anything in our surroundings depends on the notion of the observer and point of view.

Translated by: Suzana Belos