Tanja Mravak, the writer who conquered the regional cultural scene with her collection of stories Moramo razgovarati (2010) and Nasa zena (2017), is the winner of literary awards and is represented in the anthologies of the Best Croatian Story. In addition to successful artistic work, Tanja Mravak has worked for more than two decades in the Center for Autism in Split as a group leader. She is a graduate school teacher and has a master’s in special education. She has a rich professional experience, numerous professional pieces of training done, and as she says, learning in this field never stops. With Tanja Mravak, we talk about: special education as a vocation, discrepancy between theory and praxis, experience and challenges of working with children and young from that scope, changes in the community that work of the center causes, existing support, and about one that is missing in the area of the promotion of quality of life for people with autism and their families.

Tell us something about the impulse to make special education your calling, about its intertwining with other interests and hobbies?

My professional life started entirely differently. Namely, I completed education for a school teacher and worked as one shortly. Getting a full-time job as a teacher in those times, twenty-four years ago, was very difficult. On the other hand, very similar to today, special educational workers were scarce, so I worked in centers for the education and upbringing of children with special needs for a while. It was all short and episodic until, twenty-one years ago, I got employed at the Center for Autism in Split. As a matter of fact, autism is the one that determined me professionally. It was then that I started education intensely, on my own and professionally. I enrolled in and completed the study of special education alongside work when I got the opportunity. Still, learning and professional growth is ongoing process. The job truly demands a lot of giving, investment, and ample mental, emotional, and intellectual energy. Frequent revisions of the state we are in are necessary to remain professional, interested, and fresh, but at the same time fulfilled and satisfied in our private lives. Burnouts are common to all helping carriers, ours too. We need to be aware of that fact and work on ourselves, relationships, and interests outside work. In previous years, there were times when I didn’t balance private and professional with success. Now I think I’ve found an adequate rate. The first and biggest anti-stress is good relationships with people, at work as well as privately. The thing that additionally enriches me, charges and empties my batteries, is mountaineering, swimming, reading, and occasional gardening in the garden of my birth house in Sinj. Of course, writing too does that, but it requires commitment, time, and cognitive competence, which makes it difficult to name it a hobby or an interest on the side. The two books I’ve got published made me visible in the literary scene, which often means further engagements. There were periods when it was arduous to have two professional lives. It is a bit easier now I’ve learned to say no.

Is there a gap between theoretical knowledge you acquired at the special education faculty and practice? What things weren’t you taught and should have been?

So, as I have already said, I completed special education while already working, which is an entirely different position than studying without previous experience. On the one hand, much of the knowledge I gained through experience and non-systematic learning integrated into an ordered system. However, experience is something entirely personal and subjective; studies teach us to look at things objectively, to use contemporary research and knowledge. Practical work, of course, apart from lore, requires numerous other skills: resourcefulness, creativity, organization, doing several things at the same time aka, multitasking, cooperation with colleagues, professional networking, command of emotions, stress management. These are things one learns during the process of maturing. But what I would like to see worked on more and more systematically is the relationship with the parents of children with disabilities. The dynamics of the relationship between parents and professionals shouldn’t be left over to spontaneous decision-making and personal judgment.

Do you remember your beginnings? How much did your first workday correspond to your expectations?

I remember having dreams about the beneficiaries of The Center I worked with for a month. Every night, intensively. They were neutral; I cannot say they were unpleasant dreams, but I remember that period even today. And when I came to work in The Center for Autism, it was completely different from anything before. I quickly realized that my knowledge was inadequate and deficient, but back then, twenty-one years ago, knowledge about autism spectrum disorders was incomplete in our area anyway. Autism was a mystery; we learned basic work methods, like visual environmental support, through the work process. I remember considering autism a challenge, and I started learning pretty soon. I connected with a doctor who took his daughter with autism spectrum disorders to school in the United States. He provided information about new developments and work methods. And I went devotedly to any seminar, training, course, everything.

How much did the work with the children from that spectrum change you?

Much, very much. As I have already said, due to the lack of posts for teachers on the one hand and special education teachers on the other, many teachers, including myself, worked in special education jobs. To a certain degree, we prepared for work with children with intellectual difficulties at the teacher’s education faculty. Work with children with ASD was entirely unknown. Insufficient competence made me study a lot and work on myself; that was the first change I faced. The work resulted in another degree, and it is, at a certain age, quite a personal endeavor. Further on, comprehending how different we all are, how we perceive the world around us differently, all of us, not just children with ASD, and how we are the same in our basic human needs, made me a much more tolerant person. I am truly grateful for that.

When was the Center for Autism in Split founded? What were the goals, and what activities are carried out in the Center?

Center for Autism Split was founded in 1997. as a branch of The Center for Autism Zagreb. When it was founded, it had seven students in two behavioral-learning groups. Each year the number of attendees grew, and in 2018. we become independent and start functioning as an independent institution. Nowadays, in the school year 2021/22, we take care of 91 attendees in 17 behavioral-learning groups: 5 working activities groups for students older than 21; 9 groups for the extended professional procedure. Our spatial conditions are not ideal, and we are planning, with the municipality of Split, to build a new, comprehensive building. Part of that process is an upgrade of the activities of the Center. At the moment, our core activity is in the primary education field, i.e., we are implementing a program of acquiring fundamental life competencies. In addition to the program done by the leaders of behavioral-learning groups and the groups for the extended professional procedure, we conduct musical, artistic, and kinesitherapy, and psychologists and speech therapists work with the students. Before the pandemic, we had other extracurricular activities like winter holidays, summer holidays, horse riding, bowling, swimming. Hopefully, they will continue soon. Individual approach, comprehensive evaluation and assessment, visual environmental support, and procedures of applied behavioral analysis are the foundation of our professional work. The content we carry out fits into that frame, depending on the individual capabilities of each student, their life needs, and the official program frame.

What would you single out as leading principles and examples of good practice in the center’s work?

I would, most surely, emphasize the individual approach and the implementation of contemporary methods and cognition. In group work, this is not always easy; however, with the great help of our assistants, we dedicate ourselves daily to each student within their group. We have a well-educated staff with further knowledge in work therapy, sensory integration, augmentative and alternative communication, applied behavioral analysis, visual environmental support, which they share and implement.

You work in a position of a group leader. What does it practically mean, and how does your typical workday look?

A group leader takes care of three or four students of the approximate age. My students are from 11 to 15 years old at the moment. We develop an individual educational plan based on a comprehensive assessment at the beginning of each school year. We single out essential goals, short and long term. Much attention should be paid to the modification of behavior followed by the development of communication (which is very often intertwined and interdependent), and then, on this basis, develop the child’s knowledge and skills. My workday starts by coming in 15 minutes before my students, preparing tasks and activity schedules for each of them; in addition to the usual daily activities and individual independent work, they contain pair and group work when possible. Working with every student is different, different ways to communicate, a different approach, words I use. In the beginning, when you get a group of children, it is significant to estimate what motivates them, their good sides, weaknesses, what they can do on their own. The students in my current group mostly use visual environmental support on their own, which means that they can manage relatively functionally and independently through daily activities by following the visual schedule and other visual aids. Some still cannot handle that, and they need more support. In general, we work every day on reaching the set goals. That is the foundation of our work. While I work with one student, I organize the others to work on their own or with the help of an assistant. My goal is to train students for better and more competent coping in the environment that surrounds them and that everything I teach them is functional and immediately applicable. Everyday work includes quite common daily activities such as meals, hygiene, dressing, walking, going to the store, but „classic“ classroom work too, depending on the abilities of each individual student.

Do you notice changes in the treatment of children and young people with autism in the broader community? What is different today compared to when you started or the time before the establishment of the Center?

When I started to work, the word autism was associated with the automobile industry. Neither was autism recognized as a difficulty nor was the existence of the Center. People in the community noticed that the child had some problems and reacted as amateurs would, with sympathy, immature, fearfully, repulsively, depending on the situation. The situation is totally different today. The difference is not so much in behavior as in the awareness and knowledge of the broader community about autism spectrum disorders (PSA). That said, a lot more work of the people on the inside is needed: parents, professionals so persons with autism should get the treatment they deserve, the possibility of employment, assisted living, postsecondary education, etc. All of these are, it appears, in the early stages.

What prejudice about autism is the most resilient in your environment?

Oh, well, there are quite a few. The most common is a romanticized version of autism people see in the movies that these people memorize everything or are the ones living in their own world. People often ask me if I know someone who knows the dates or capital cities by heart. That is something they find interesting. The answer is yes, I have had such students, but some other things define them more.

Is there any prejudice about the special educator profession? Is your work sometimes underestimated or exposed to groundless expectations?

I have mixed feelings about that. A lot of people in the surroundings don’t even have a clear idea about the job. We needn’t search far; my father, to the day, thinks that I look after sick children. I would say that the scope of our work is not recognized, but generally, it is not underestimated. The expectations are always huge; that is something we should take care of, particularly young colleagues. It is very important to know how far our competencies and potential reach. Parents have the right to expect their child’s progress; it is up to us to invest our knowledge and professional commitment in it but also to communicate with each other clearly and with respect.

Do you ever wish to quit the job? If yes, what are the reasons? If not, what is your prime motivation?

Well, I cannot say that I want to stop the work I’ve been doing, but I wish the conditions were much better. Sometimes I see the capabilities of my students, and I cannot do anything to help them realize their potential because I simply don’t have enough time or overall financial backing. It can frustrate me a lot. I learned, in time, it isn’t my fault or responsibility; I give what and how much I can. Still, there is regret for a better system, more money, more care from the state. However, we all make the system, and we have to resist the urge to give up everything because not everything is ideal. The motivation? I am very interested in autism, its neural basis, incredible diversity, and the way a person with ASD experiences the world. I am really, sort of speak, immersed in it. And baby steps of the progress of my students.

Has pandemic caused some additional pressure and challenge? How did the Center function during restrictive measures and quarantine?

Of course, it has! I have never felt so senseless in my working history than during those two months working from home. In the spring of 2020. we worked, like everyone else, from home. My job is to catch the subtle signs of progress, communicate intentions, follow precisely how much support to give to a child, and when is the right time to deny it. All of these demands focus, concentration, and before all, physical presence. I am saying, once again, I have never felt such hopelessness, senselessness, and futility as during online schooling. It did – not to paint everything black, had its plus sides. I cooperated with the parents much more in the homework department, i.e., functioning in everyday conditions. As a result, they started applying things I would have a hard time making them do in ordinary circumstances, or it just wasn’t in focus. After those couple of months, even while schooling in the rest of the system stayed online, we continued the work live. With great care, implementing epidemiological measures, canceling all extracurricular activities, but live. And so, until the omicron appeared, we didn’t have a significant breakthrough of the virus into the Center. Hence, we believe that we have successfully weathered the epidemic so far.

How much attention is paid to the mental health of persons with autism and the well-being of their families? Is there professional staff to provide psychological support or treat depression, anxiety, and other challenges people on the spectrum face? Or do other health issues stay suppressed by primary diagnosis?

I am afraid that this problem is not addressed as it should be. Firstly, I’d like to refer to care for the parents and family in general. And it is either nonexistent or left to associations and project programs. It is not a way to systematically help persons with ASD families combat issues specific to this condition. I fear that the system providing care for the mental health of parents and siblings of persons with autism is nonexistent. The other one that influences mental wellbeing is nonexistent too. Parents wonder for a long time before the child gets a diagnosis, then they feel lost among various experts, therapies, treatments. The early intervention system is still in its infancy and the part that functions demands a lot of educated personnel. Today’s situation is that a child could be referred to a rehabilitator or a speech therapist, but let’s say once in a fortnight. It means nothing; it is symbolic. Parents are additionally exhausted financially by paying for various experts, but there is nothing else they could do. When you then read that there are systems where parents, in addition to comprehensive early intervention, also get someone to look after their child to go to the hairdresser or wherever they wish to, or they want to have serious expert help, one cannot avoid frustration. When persons with autism are concerned, anxiety is their constant companion. Life around them is chaotic, without order and routine, unpredictable and unsteady; they are in a permanent state of anxiety. Adolescence is a particularly challenging period. It appears that we perceive the problem only when it escalates through undesirable behavior. In the area of Split and the county, there are not enough children and adolescent psychiatrists. I also think that occasional education on the mental health of people with autism should be a common practice for professionals of all profiles working with people with ASD. I witness the problem with children in the regular school system; the challenges set before them and the colleagues in the professional school services are really great.

We usually deal with children when we talk about autism. What possibilities for independent living are there for adults with autism in Split?

Yes, we rarely hear about adults with autism, as if after twenty, their autism ceases to exist. We, too, due to legal limitations, were dealing only with education, but a process is underway that would allow us to take broader action, i.e., to introduce content from the social welfare domain. There are social welfare institutions that deal with adults with difficulties, including persons with autism but I fear that the system’s care about adults concerning employment and independent living is absent or weak. I must say, however, that this is not just a question of autism. It is a matter of caring for all adults with disabilities, for which there is a relatively good legislative framework, but in implementation, we still encounter numerous and permanent obstacles.

Does your professional engagement influence the literature you create? How does a special education teacher communicate with a writer?

There is a story about a boy with autism from the beginning of my writing carrier. That is actually all. Later I had some constraints which I couldn’t explain rationally. As if writing about autism, I would use something I have no right. I am changing the view now; it feels I could contribute to better visibility and understanding about the life of persons with autism and their families.

What would you say to a junior colleague starting to work with children from the specter?

What I tell them when they come: – It won’t be easy, each time it is not, come. I advise junior colleagues gladly, warn some of them to slow down, not to forget about the balance between private and professional life because if they suffer from burnout, they won’t be of any help. However, it is a road each person has to take on their own. My duty as a senior colleague is to provide support and give a hand when they slip. And to learn from them too, they come fresh, full of enthusiasm, with some new learning, it is a source of energy we must not neglect.

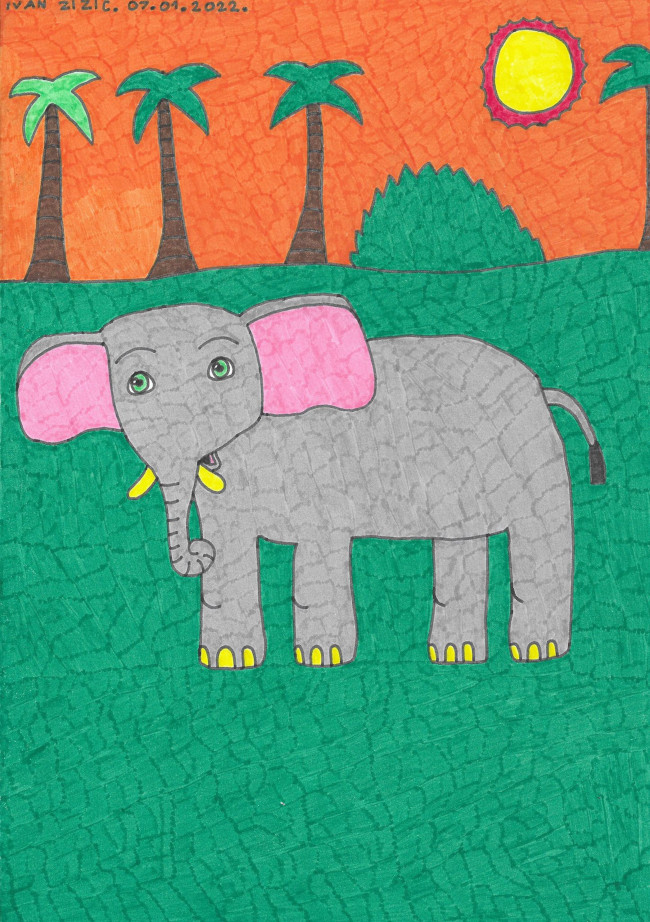

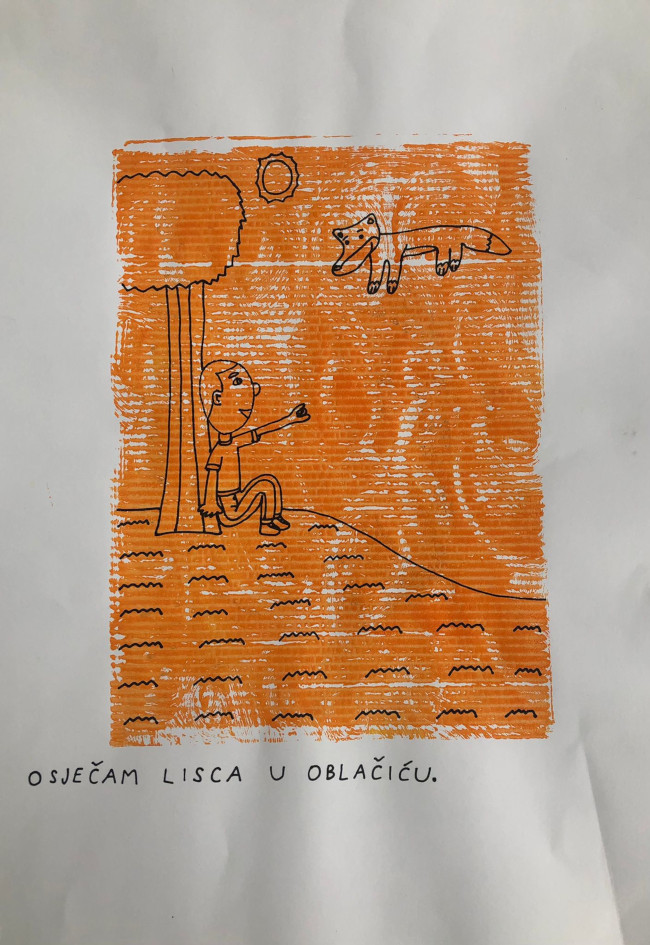

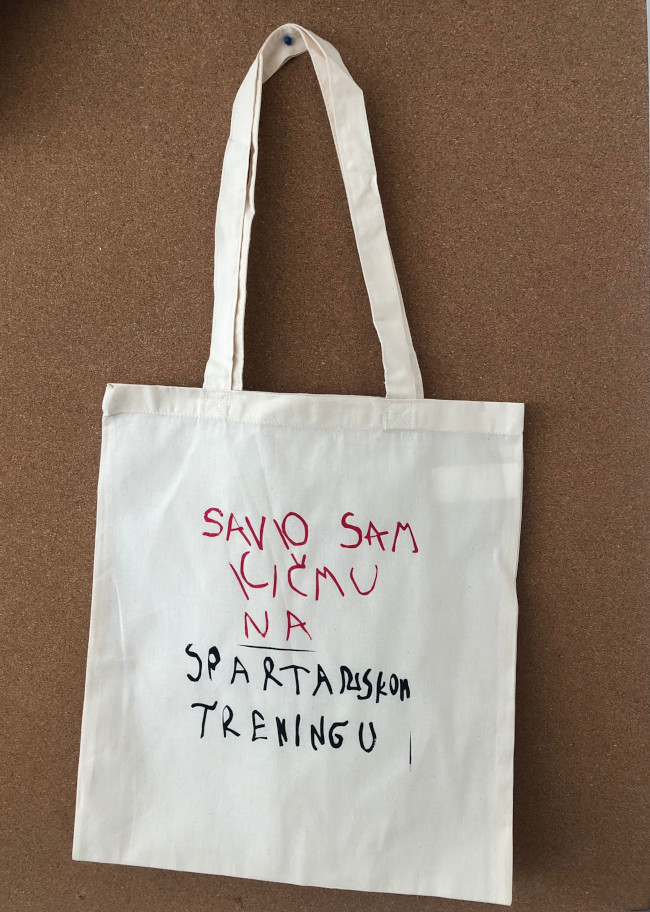

Photographs: Works of children and young from the specter within activities of The Center for Autism Split